How Park Chan Wook Turned Hollywood's Rejection Into His Most Urgent Film

Park Chan wook spent over a decade trying to make an American adaptation of Donald Westlake's 1997 thriller "The Ax." He pitched it to multiple Hollywood studios, believing the story about a laid off worker murdering his competition deserved an American setting. Every studio passed. They couldn't see the commercial potential in a dark comedy about unemployment, corporate greed, and economic desperation. One after another, they turned him down.

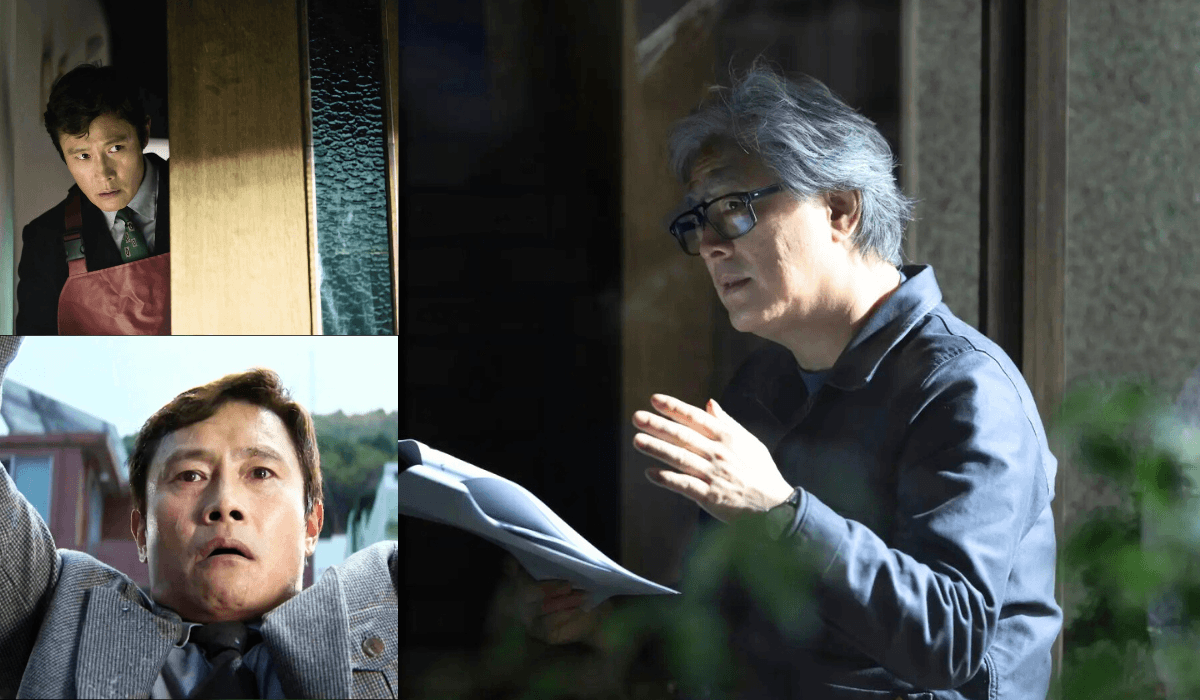

The director of "Oldboy" and "The Handmaiden" recently confessed he almost thanked those studios in the credits of "No Other Choice," the Korean adaptation he finally made after Hollywood rejected him. He reconsidered at the last minute, but the impulse reveals how dramatically the rejection improved his film. Forced to reimagine the story for South Korea, Park created what many critics are calling his most humane, mordantly funny, and devastatingly timely work. Hollywood's loss became cinema's gain.

"No Other Choice" premiered at the Venice Film Festival in August 2025 to a nine minute standing ovation. It swept through festival circuits, winning Toronto's People's Choice Award, earning three Golden Globe nominations including Best Foreign Language Film, and becoming South Korea's official Oscar submission. The film grossed over 22 million dollars worldwide despite its dark subject matter, and currently holds a 99 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes from 126 reviews. Critics have called it everything from a masterpiece to Park's sharpest workplace satire to the best directed film of 2025.

The story is brutally simple. Yoo Man su, a paper factory manager, loses his job after 25 years when American investors restructure the company. He job hunts for over a year with no success. Desperate to maintain his family's comfortable life, he realizes the only way to beat his competition is to eliminate them literally. He tracks down the other qualified candidates through a fake job listing, then systematically murders them one by one.

What elevates "No Other Choice" beyond premise is Park's tonal mastery and his willingness to make audiences complicit in Man su's logic. This isn't a straightforward thriller where we root against a villain. It's a pitch black comedy that forces us to understand, if not excuse, why an ordinary decent person might conclude murder is his only option. That's exponentially more unsettling than simple violence.

When Rejection Forces Better Art

Park's journey with this material demonstrates how constraints often produce superior results. He discovered Westlake's novel decades ago and immediately recognized its cinematic potential. Costa Gavras had already adapted it in 2005 as "Le Couperet" (The Axe), a French language film starring José Garcia. But Park believed the story's DNA was fundamentally American, rooted in that country's particular brand of corporate capitalism and disposable workforce culture.

He spent years developing an American version, writing drafts with Canadian screenwriter Don McKellar among others. He imagined filming in suburban America, casting American actors, and making his English language debut. The pitch meetings went nowhere. Studio executives either didn't understand the tonal tightrope Park wanted to walk, mixing slapstick comedy with genuine horror, or they couldn't see how to market such a morally complex story about economic anxiety and murder.

Their rejection forced Park to reconsider everything. Rather than simply translating the story to Korea, he reconceived it entirely for that context. Korean culture's relationship with work, family honor, and middle class respectability differs substantially from American equivalents. The shame of unemployment cuts deeper. The pressure to provide creates different breaking points. The rigid hierarchies and expectations shape how desperation manifests.

Most crucially, setting the story in 2025 Korea allowed Park to incorporate anxieties that didn't exist in 1997 when Westlake wrote the book. Man su doesn't just compete against other humans for jobs. He's competing against AI and automation. Park added a devastating final realization: even if Man su successfully eliminates all his human rivals, machines will ultimately replace him anyway. That addition transforms the story from period piece social commentary into urgent present tense alarm bell.

The casting similarly benefited from the forced change. Park got Lee Byung hun, one of Korea's finest actors, known internationally for "Squid Game" but possessing range and depth Hollywood rarely allows Asian actors to display. Lee brings desperate intelligence and broken pride to Man su, making him simultaneously sympathetic and monstrous. Viewers understand his reasoning while recognizing its horror.

Son Ye jin plays his wife Mi ri with devastating subtlety. She's not the supportive wife cliché or the nagging partner who doesn't understand. She's a woman managing her own terror about their future while trying to keep her family functional. Her performance gives the film its emotional anchor, reminding us of the real human cost beyond Man su's increasingly abstract moral calculations.

The supporting cast, including Park Hee soon, Cha Seung won, Lee Sung min, and Yeom Hye ran, create fully realized victims rather than disposable plot devices. Each person Man su targets represents someone with their own desperate circumstances, their own families depending on them. Park refuses to let us forget that Man su's solution to his problem simply transfers that problem to someone else, multiplying suffering rather than resolving it.

Park's Visual Mastery and Tonal Control

What separates "No Other Choice" from competent thrillers is Park's extraordinary command of visual storytelling and his ability to modulate tone with precision. The film opens in saturated happiness, Man su's family picnicking outside their beautiful home, children laughing, dogs playing. Park shoots it like a commercial for an idealized life, all bright colors and perfect composition. Then storm clouds literally roll in, darkening the frame before the first edit.

That visual metaphor might seem heavy handed from a less skilled filmmaker. Park makes it work through sheer conviction and the contrast with what follows. Once Man su loses his job, the visual palette shifts. Colors desaturate. Spaces feel colder. The comfortable home becomes oppressive as financial pressure mounts. Park uses environment to externalize psychological states without dialogue, trusting cinematographer Kim Woo hyung to capture the emotional architecture.

The murder sequences demonstrate Park's tonal genius. The first attempt goes comically wrong, with Man su slipping in mud, getting bitten by a snake, and confronting an angry woman with her own gun. It plays like slapstick, recalling Park's description of the film as "a vicious episode of Looney Tunes." The violence feels absurd rather than threatening.

Then the second murder succeeds, and the tone shifts dramatically. Park stages it with casual efficiency that's genuinely chilling. Man su has learned from his mistakes. He's better at killing now, more systematic. The comedy doesn't disappear entirely but becomes darker, more uncomfortable. We're laughing at things that shouldn't be funny, implicating ourselves in the horror.

The scene critics keep citing involves Man su preparing to shoot a sleeping man. He wraps the gun in plastic, covers his hand with oven mitts to prevent powder burns, and cranks up music to mask the sound. The man wakes up before Man su can fire. Rather than fleeing or fighting, they argue about the victim's relationship with his wife while upbeat music blares. Man su criticizes the man for never listening to his wife's advice, defending the woman who's currently sneaking up behind him with a weapon.

The sequence is simultaneously hilarious and horrifying. The domestic advice feels genuinely caring. Man su means it when he says the man would be happier if he just listened to his wife. But he's saying it while preparing to murder him. The cognitive dissonance is profound. Park stages it with impeccable blocking and timing, characters moving through the frame in choreographed chaos that resolves into violence.

Park's camera placement throughout demonstrates why critics call him a master. He always knows exactly where to put the camera, how long to hold a shot, when to cut. There's a sequence where Man su drinks a boilermaker that reviewers described as "one of the most intoxicating and thrilling images of 2025." It's just a man drinking a drink, but Park shoots it with such purpose and compositional beauty that it becomes almost erotic, capturing the relief and escape alcohol provides.

The visual precision extends to smaller moments. Man su's habit of writing notes on his hand becomes a recurring motif. The way sunlight blinds him at key moments develops into something between practical difficulty and metaphorical judgment. These details accumulate without requiring explicit payoff, creating texture rather than neat closure. Park indulges in pure cinema, letting images exist for their own aesthetic and emotional value rather than only serving plot.

The AI Apocalypse Lurking Beneath

The most devastating addition Park made to Westlake's story involves artificial intelligence and automation. In the novel, Burke Devore eliminates his human competition and gets the job. Success feels hollow and morally poisoned, but it's still success. Park denies Man su even that corrupted victory.

The director explained that when he first encountered the source material, the threat was purely human versus human. Workers competed against other workers for scarce positions while management profited. That dynamic still exists, but it's no longer the final threat. Now workers face elimination not by other desperate people but by machines that don't need salaries, benefits, healthcare, or rest.

Park's addition of AI as the ultimate competition transforms the film's meaning. Man su goes through the entire moral descent, murders multiple people, destroys his own humanity, only to realize at the end that he's been fighting the wrong enemy. The real threat isn't other workers. It's the system that treats workers as disposable regardless of their skills, experience, or dedication.

The final sequence shows Man su celebrating alone in an automated paper mill. Machines do all the work humans once performed. He's technically employed, but isolated and useless, overseeing processes that don't require human oversight. The image crystallizes everything the film has been building toward. Corporate restructuring isn't about efficiency or competitiveness. It's about eliminating workers entirely while extracting their remaining value.

This resonates profoundly in late 2025 as AI anxiety reaches fever pitch. Daily headlines describe new industries facing automation. Artists, writers, programmers, customer service representatives, truck drivers, entire categories of employment face potential obsolescence. Westlake's 1997 novel asked what happens when companies decide workers are disposable. Park's 2025 adaptation asks what happens when companies decide workers are unnecessary.

The film doesn't offer solutions because Park doesn't have any. He's diagnosing rather than prescribing, capturing the specific terror of our moment when the future of work feels apocalyptic. The title "No Other Choice" applies not just to Man su's moral descent but to the structural reality forcing that descent. Under capitalism that treats labor as cost to be minimized rather than partnership to be valued, workers genuinely have no other choice but to savage each other while the system crushes them all.

Class Warfare Turned Inward

What makes "No Other Choice" more insightful than most eat the rich satires is its refusal of simple class binaries. Man su isn't poor. He's solidly middle class, or was until unemployment. His targets aren't wealthy elites but other middle class workers in identical circumstances. This is class warfare turned inward, the have somes attacking each other while the actual wealthy profit from the carnage.

Park explained that unlike "Parasite" and similar films that provide catharsis through us versus them dynamics, "No Other Choice" offers only despair. There's no satisfying revenge against the rich. There's no class solidarity leading to revolution. There's just desperate people clawing at each other for scraps while the system that created their desperation remains untouched and unchallenged.

This perspective feels more accurate to contemporary economic reality than triumphant class war fantasies. Workers don't unite against ownership. They compete against each other for the privilege of continued exploitation. Management encourages this competition, framing it as meritocracy. The best workers get to keep working. Everyone else is simply not good enough, not committed enough, not flexible enough.

Man su internalizes this logic completely. He doesn't blame the American investors who restructured his company. He doesn't organize with other laid off workers to demand better treatment or social safety nets. He accepts the premise that only the strongest deserve employment, then simply decides to make himself the strongest through murder. It's the ultimate expression of individualist ideology taken to its darkest conclusion.

The film's refusal to provide moral clarity or satisfying catharsis frustrates some viewers. They want Man su clearly condemned or redeemed. They want the system clearly attacked or defended. Park gives them neither. He shows us a man broken by circumstances many of us could face, making choices we hope we'd never make, revealing how thin the line between civilization and savagery really is when security disappears.

Personal Perspective: The Uncomfortable Mirror

Honestly, "No Other Choice" disturbed me more than any horror film this year. Not because of the violence, which is relatively restrained compared to Park's earlier work. Because of how completely I understood Man su's reasoning. That's the film's terrible achievement. It makes murder comprehensible without making it acceptable, forces us to follow the logic of desperation to its conclusion.

I've never been laid off after 25 years of loyal service. I haven't faced the specific pressures Man su navigates. But I live in the same economic system that treats workers as disposable. I've watched colleagues fired via email. I've seen entire departments eliminated with three weeks notice. I understand the precarity that defines contemporary employment, where decades of service guarantee nothing and loyalty flows only one direction.

Park's genius is making us sit with the discomfort of recognizing ourselves in Man su. We're not murderers. We haven't crossed those lines. But have we not felt the same resentments, the same anger at systems that value profit over people? Have we not looked at competition for scarce resources and wished it would simply disappear? The film holds up a mirror we'd rather not look into.

The tonal whiplash between comedy and horror amplifies this discomfort. I found myself laughing at scenes that should have appalled me, then feeling guilty for laughing. That's precisely Park's intent. He wants us implicated, wants us questioning our own moral certainties. It's easy to judge Man su from safety. Would we judge him as harshly if we were drowning in the same desperation?

I also appreciate how the film depicts Man su's family without sentimentality. Mi ri isn't a saint patiently supporting her husband. She's scared and frustrated, making pragmatic decisions about expenses, suggesting they sell the house Man su fought so hard to reacquire. His children react to stress in realistic ways, becoming withdrawn or acting out. The dogs, beloved family members, get sent away because they can't afford to keep them. These small domestic losses accumulate into genuine tragedy.

The film's visual beauty creates additional cognitive dissonance. Park's frames are gorgeous, meticulously composed, a pleasure to watch. This subject matter probably shouldn't look this beautiful. But the aesthetic control makes everything more disturbing, not less. It's the difference between witnessing chaos and watching chaos choreographed by a master. The latter is somehow more unsettling because it suggests order underneath, logic beneath the horror.

What Hollywood Missed

American studios that rejected Park's adaptation made a spectacular miscalculation. They couldn't see the commercial potential of a film about economic anxiety and unemployment. Yet "No Other Choice" proves audiences absolutely want smart, challenging cinema that grapples with the systems shaping their lives. The film's success, both critical and commercial, demonstrates that mainstream viewers are hungrier for substance than executives believe.

Hollywood's risk aversion increasingly means the best films about America get made elsewhere. "No Other Choice" captures something essential about late stage capitalism, the precarity and desperation defining contemporary work life, more incisively than most American films dare. Park saw that universality in Westlake's novel. Studio executives saw only a downer that couldn't sell.

Their loss extends beyond this specific film. By rejecting Park repeatedly, they lost the opportunity to work with one of cinema's great visual artists at the height of his powers. They could have had an English language Park Chan wook film, with his compositional genius and tonal mastery applied to American stories. Instead, Korea gets another masterpiece while Hollywood produces another round of franchise extensions and franchise extensions.

The rejection also reveals how terrified studios are of genuine social commentary. "No Other Choice" isn't subtle about its targets. It directly indicts corporate practices that treat workers as expendable. It shows the violence inherent in a system that forces desperate people to compete for survival. Hollywood executives apparently couldn't imagine American audiences wanting to confront that reality, even in the safely distanced form of entertainment.

They were wrong. The film's reception proves audiences recognize themselves in Man su's situation even if they've never considered his solutions. Economic anxiety transcends nationality. The fear of obsolescence, of being discarded after decades of dedication, resonates across cultures. Park understood that universality. Hollywood missed it entirely.

Lee Byung Hun's Career Best Performance

Much of the film's success depends on Lee Byung hun's extraordinary performance as Man su. Lee is internationally known for "Squid Game" and franchise appearances in films like "GI Joe," but those roles barely hint at his range. "No Other Choice" provides a showcase for his complete toolkit, requiring him to be simultaneously desperate, intelligent, sympathetic, methodical, and monstrous.

The performance works because Lee never plays Man su as a villain. He's an ordinary man in impossible circumstances making terrible choices incrementally. Each moral compromise feels logical given the previous one. Lee captures how quickly the unthinkable becomes thinkable when survival is at stake. His face registers micro expressions of shame, determination, fear, and grim humor, often simultaneously.

Critics are calling it the most underrated performance of 2025, suggesting Lee deserves awards consideration but likely won't receive it due to the film's dark subject matter and foreign language status. That would be a shame. This is precisely the kind of technically demanding, emotionally complex work that deserves recognition. Lee makes us care about someone who becomes a serial killer, maintaining our investment even as Man su crosses lines we hope we'd never cross.

The scene where Man su first successfully commits murder demonstrates Lee's skill. He doesn't play triumph or relief or satisfaction. He plays a man doing an unpleasant but necessary job, like fixing a leaky pipe or filing taxes. The horror comes from that mundane efficiency, the way murder becomes just another task to complete. Lee gives us just enough humanity to make Man su relatable while never letting us forget what he's doing is monstrous.

Son Ye jin matches him beat for beat as Mi ri. Their chemistry feels lived in, the comfort and tension of a long marriage under extreme stress. She's not a passive victim or supportive angel. She's actively managing the family's collapse, making hard choices, trying to protect their children from understanding how bad things are. The relationship feels real in ways Hollywood rarely achieves, complicated and messy and essential.

The Film Park Needed to Make

Watching "No Other Choice," it becomes clear this is the film Park needed to make right now, at this moment in his career and the world's trajectory. His earlier work, particularly the Vengeance trilogy, explored violence and revenge in more operatic, stylized forms. Those films are masterpieces of their kind, but they exist in heightened reality where catharsis through violence feels possible.

"No Other Choice" operates in mundane reality where violence solves nothing. Man su's murders don't actually fix his problems. They just create new problems while destroying his soul. There's no catharsis, no satisfaction, no sense that justice has been achieved through extreme means. There's only horror at how far desperation pushed him and despair at the systems that created that desperation.

This feels like Park's angriest film, the most directly political despite not being overtly political. He's not making arguments about specific policies or candidates. He's diagnosing the fundamental sickness of economic systems that treat human beings as disposable inputs to be optimized. That diagnosis feels urgent in 2025 as AI anxiety peaks and workers face unprecedented challenges to their continued relevance.

The timing of the film's release, arriving Christmas Day 2025 in U.S. theaters, adds dark irony. It's counterprogramming against holiday fare, offering audiences economic horror instead of seasonal comfort. But it's also perfectly timed to capture end of year anxiety, the way December forces reflection on the year past and dread about the year ahead. For anyone experiencing job insecurity or watching industries transform around them, "No Other Choice" will feel painfully relevant.

The Best Possible Version

Hollywood's rejection forced Park Chan wook to make a better film than he originally imagined. The Korean setting, the AI additions, the specific casting, all of it flows from being denied his first choice. Sometimes constraints produce superior art. Sometimes what seems like failure at the time becomes blessing in retrospect.

"No Other Choice" stands as one of 2025's essential films precisely because of its refusal to comfort or simplify. It forces audiences to sit with uncomfortable realities about work, class, and the violence underlying systems we take for granted. It's brilliantly made, featuring Park at his visual peak and Lee Byung hun giving the performance of his career. But it's also deeply unsettling, leaving viewers shaken rather than entertained.

That's as it should be. A film about economic desperation shouldn't make us feel good. It should make us recognize the desperation exists, understand what drives it, and question the systems perpetuating it. Park achieves all that while still delivering the pleasures of craft, the satisfaction of watching a master filmmaker exercise complete control over every element.

The studios that rejected him should watch what they missed. They couldn't see past their own assumptions about what audiences want. Park proved them wrong by making exactly the challenging, uncompromising, devastatingly relevant film they feared. Sometimes no other choice turns out to be the best choice possible.