How To Recover From A Bad FreeCell Start

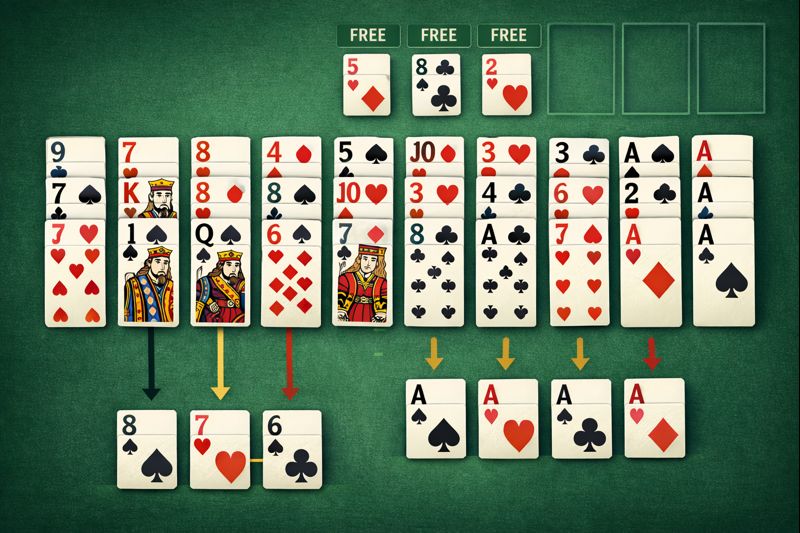

A bad start in FreeCell Solitaire can feel discouraging. The Aces are buried, free cells fill up too fast, and there seems to be no space to work. It looks like the game is lost before it even begins. In truth, a bad start is not a dead end; it is simply a situation that requires patience, planning, and controlled thinking. These are the games where FreeCell becomes more than a card game and turns into a true strategy puzzle.

Winning from a bad start is about creating freedom. Freedom of movement, freedom of choice, and freedom to correct mistakes. This article explains how to build that freedom step by step.

What Makes a FreeCell Start “Bad” and How Should You Think About It?

A bad start is defined by restriction, not by impossibility. The board gives you fewer obvious moves and punishes careless ones.

Understanding the nature of a bad start

A position usually feels difficult when the Aces and low cards are buried under many layers, the columns are long and tangled, there are no empty columns, and the free cells fill very quickly. None of this means the game cannot be solved or that you do not know how to win FreeCell Solitaire. It only means that your early moves must be more precise and more thoughtful than usual.

Before making any move, pause and look at the entire board. Find where the Aces are hiding, notice which columns are shortest, and observe which suits seem trapped and which ones are more flexible. Learning how to win FreeCell Solitaire begins with this observation phase, because it is what separates strategic play from random play and turns difficult starts into manageable challenges.

Developing the right mindset

Bad starts demand calm. Panic leads to filling free cells without a plan and sending cards to the foundations too early. Instead of trying to “do something,” your first goal should be to understand the position. In FreeCell, control comes before progress.

How Do Free Cells and Empty Columns Give You Control?

Free cells and empty columns are the heart of recovery. They decide how powerful your position is and how easily you can reorganize the board.

Using free cells with intention

Free cells exist to create temporary space. They help you remove blocking cards, uncover low cards, and rearrange sequences, which is a key part of understanding how to play FreeCell Solitaire effectively. The biggest mistake is treating them like permanent storage. Once all free cells are filled, your flexibility disappears and the game becomes much harder to control.

A simple rule keeps you safe: try to always leave at least one free cell empty. That single empty space often allows you to escape traps and create new opportunities, and it is one of the most important principles in learning how to play FreeCell Solitaire with confidence and strategy.

Why empty columns change everything

Empty columns are stronger than free cells because they can hold entire sequences instead of single cards. They let you move large blocks of cards and completely reshape the board. In many bad starts, the moment you create one empty column is the moment the game begins to turn in your favor.

Understanding your moving capacity

Your ability to move cards depends on the space you control:

(Max movable cards) = (Free cells + 1) × (Empty columns + 1)

This means that every free cell and every empty column multiplies your power. When you feel stuck, the real problem is usually not the cards themselves, but the lack of space to move them.

How Should You Use Foundations and Low Cards During Recovery?

Foundations are the final goal, but in bad starts they must be approached carefully. Moving cards upward too early can remove useful building pieces from the tableau.

Treating foundations as permanent storage

A card should go to the foundation only when you are confident it will not be needed again. If that card could help build a sequence or support future moves, it is better to keep it in play. Foundations are safe zones, not quick exits.

Why low cards unlock the game

Low cards are the true engine of progress. Aces, 2s, 3s, and 4s create structure and reduce complexity. Most Unwinnable FreeCell Games are won by digging downward to free these cards, not by pushing high cards upward.

Uncovering low cards:

- Opens foundations safely

- Simplifies the tableau

- Creates stable building points

Each Ace you uncover removes one suit’s worth of future obstacles. That is why freeing Aces is often more important than making visible progress.

How Do You Replace Chaos with Structure?

A bad start feels chaotic because the board lacks organization. Your task is to build structure gradually.

Building strength through alternating sequences

Long descending sequences in alternating colors are the backbone of stability. They allow you to move multiple cards at once and make it easier to create empty columns. Even when suits do not match perfectly, alternating colors still bring order to disorder.

Keeping suits and colors balanced

If one suit becomes trapped or one color dominates the board, future moves become limited. You should try to free buried suits early and avoid stacking too many cards of the same color together. A balanced board is a flexible board.

Knowing when to break a sequence

Not every clean-looking sequence is helpful. A sequence becomes harmful when it blocks access to low cards, forces all free cells to fill, or prevents you from creating an empty column. Breaking such a sequence may look like a setback, but it is often a strategic reset that opens new paths.

How Do Patience, Backtracking, and Flow Lead to Victory?

Bad starts rarely unfold smoothly. They are solved through experimentation and correction.

Why backtracking is part of smart play

Undoing moves is not weakness. It is how you explore possibilities without permanent risk. Skilled players backtrack often because they understand that the first solution is not always the best one.

A natural recovery flow

Most successful recoveries follow a pattern:

- Protect at least one free cell

- Search for an Ace or another low card

- Begin foundations carefully

- Build one strong alternating sequence

- Create an empty column

- Expand your moving capacity

- Let the board open naturally

Once flexibility is established, progress becomes much faster and more intuitive.

Staying calm during difficult positions

FreeCell rewards patience. When free cells fill, do not panic. When a plan fails, undo and try again. Think of different types of freecell and it's several moves ahead and accept that temporary disorder is sometimes necessary to achieve lasting control.

Final Thought

A bad FreeCell start is not a sign of defeat. It is an invitation to play with depth, logic, and precision. When you learn to value space, respect free cells, seek empty columns, uncover low cards, and stay patient, difficult layouts stop feeling frustrating. They become the most rewarding games you can play, because every victory feels earned through understanding rather than luck.